Nuclear Security - Full Report

Summary

Why focus on this problem?

We have been living in a world of nuclear weapons since 1945. We have been incredibly fortunate that these weapons have not been used in anger since then, but we believe the world is dangerously complacent about the risks of a nuclear conflict. The threat of nuclear war doesn't raise the same amount of public attention as it did in the cold war, but the risks are just as great today, if not more so. Although there is an appearance of nuclear stability, nuclear command and control systems are surprisingly vulnerable to fatal errors from individuals, cyber attacks, and equipment malfunctions. We believe there is much we can do to solve these problems - after all, humans created this problem and humans can solve it.

Thoughtful and non-controversial policies could substantially reduce the risk of a nuclear exchange. Moreover, a nuclear-weapon-free world is a world closer to the kingdom of God. Christians are called to be peacemakers. A nuclear exchange would cause a humanitarian disaster with widespread sickness, famine and destruction, on a scale unprecedented in history. Even though a nuclear war is not certain, the magnitude of disaster if it should happen means it is well worth our attention.

Statue outside the UN headquarters in New York. “They shall beat swords into ploughshares” - Is. 2:4

Evan Schneider/Creative Commons

What Does An Impactful Career In Nuclear Security Look Like?

Nuclear Security Careers Can Be Highly Impactful

We think nuclear security careers are important for one simple reason: a nuclear war would be really, really bad! And we think that the right person, with persistent effort and smart career decisions, might be able to make the world just a little bit safer from this threat.

Let’s put the numbers into perspective. The Second World War was the deadliest conflict in history so far, claiming maybe 60 million lives. The worst humanitarian disaster in history was the Black Death, which claimed as many as 200 million lives in Europe. The death toll of a full nuclear war between the USA and Russia would swamp both of those, with estimates as high as 5 billion or more . In these models, the bulk of the damage comes from a nuclear winter, where ash and soot released into the atmosphere block sunlight, causing a global crop failure and famine.

Given how bad nuclear war would be, we think many more people should be working to reduce this risk relative to other problems. Whilst there are always strong and valid reasons for people choosing not to work on a problem, other reasons don’t always stand up to scrutiny.

People are often misled by cognitive biases and simplified narratives, such as “A nuclear war has never happened before, so it probably won’t happen in the future”. Sadly, this is not valid reasoning! As every financial advert disclaims, ‘past performance is no guarantee of future results’.

Another misleading narrative might be “These issues are so big, there’s nothing I can do about it”. Well, the issue certainly is a big one. But rather than believing ‘I can’t do anything’, it might be more accurate to believe ‘I could be able to do something’.

Others might ignore nuclear security because it seems like an old-fashioned concern: the sort of thing people worried about in the sixties, not nowadays when we have glamorous new problems like climate change and AI to deal with. Unfortunately, this doesn’t work either. Even though news coverage has gone down, the potential for destruction remains just as high as in the sixties, if not more so (mainly due to destabilising changes in geopolitics and technology).

History shows that a single individual in the right place at the time can make an enormous difference to nuclear security. Take the story of Stanislav Petrov, a Lieutenant Colonel in the Soviet Army during the Cold War. In 1983, Petrov was on duty in a Soviet missile base when early warning systems apparently detected an incoming missile strike from the United States. Protocol dictated that the Soviets order a return strike. But Petrov didn’t push the button. He reasoned that the number of missiles was too small to warrant a counterattack, thereby disobeying protocol.

If he had ordered a strike, there’s at least a reasonable chance hundreds of millions would have died. The two countries may have even ended up engaged in an all-out nuclear war, leading to billions of deaths and, potentially, the collapse of civilisation. Of course, we can’t all expect to be in Petrov’s position, but God may well have plans to use you to do great good.

Of course, there are some good reasons for not working on this problem nonetheless, and we shall discuss these later on.

It’s really hard to know how much impact you will have with your career, as the world is so uncertain. In the words of the apostle James, “you do not know what tomorrow will bring”! (James 4:14) Nonetheless, at Christians for Impact we think you can drastically increase your career impact on average by using reason and good judgement when deciding what to work on. Moreover, we think working to improve nuclear security is on average much more impactful at reducing conflict and humanitarian disasters than almost any other career. But whether this is true for you crucially depends on your personal preferences, talents, and calling.

The Past, Present And Future Of Nuclear Weapons

“ This is the nearest thing to doomsday that one could possibly imagine. I am sure that at the end of the world — in the last millisecond of the Earth’s existence — the last human will see what we saw. ”

— George Kistiakowsky, after watching the Trinity test (July 16th 1945)

Scientists first learned to split atoms apart with high energy particles in the early 1930s. Experiments with the fission of uranium atoms found two things. First, an astonishing amount of energy was released. Second, the neutrons released from the splitting of one uranium atom could be used to split even more atoms. It didn’t take long for nuclear scientists to realise that assembling a critical mass of uranium atoms could cause an explosive chain reaction. As the Second World War began, it was clear that developing a nuclear weapon could grant a decisive military advantage. Although the Nazis abandoned their efforts in 1942, the US’s Manhattan project succeeded and culminated in the first nuclear bomb being dropped on Hiroshima on 6th August 1945, and a second on Nagasaki on 9th August.

After the Second World War, an arms race broke out between the USA and USSR. Although no weapons were ever used in anger, both sides developed and tested ever larger bombs. By 1952, the US had tested the first hydrogen (a.k.a. thermonuclear) device with an explosive yield 450x greater than the Nagasaki bomb. A typical US warhead today is at least 5x more powerful than the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs, and a Trident missile may contain as many as 12 such warheads.

Thankfully, the nuclear arms race cooled down in the late twentieth century. The NPT (non-proliferation treaty) limited the number of nuclear capable states - whereas 19 states were possessing, pursuing, or considering nuclear weapons in 1987, only 9 states have nuclear capabilities today. Arms reduction treaties between the US and Russia and the end of the Cold War helped to reduce the total number of warheads in operation.

However, this is no cause for complacency. Tensions between Russia and the US are currently high, especially since the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, and prospects for future arms reductions are poor. The New START arms control treaty expires in 2026 and cannot be renewed without renegotiation. Moreover, China is rapidly growing its nuclear arsenal. Many experts are concerned that the emergence of China as a third major nuclear power will be destabilising, as it is harder to make agreements between three parties than with two. More discussion can be found in this report. The risks are not just limited to traditional superpowers - there’s also a risk of escalation or misuse from other nuclear-capable states such as North Korea, or Pakistan and India.

There are two predominant threat models of how a nuclear war might begin. One is a nuclear escalation of a conflict (such as the war in Ukraine), and the other is an accident or misuse of nuclear weapons. These two threats can exacerbate each other. Accidental use of nuclear weapons is more likely to happen during a tense moment in a conflict when nerves are jittery, whilst accidental confrontations could cause a conflict to escalate. For example, accidental use of nuclear weapons was more likely during the Cuban Missile Crisis because commanders on both sides were under high pressure and unsure of the strategic situation.

In the future, we could see these threats exacerbated by destabilising new technologies. Rapid progress in offensive cyber capabilities, or rapid progress in generative AI could be used by hostile state or non-state actors to undermine nuclear command control and communications (NC3) systems. For example, human operators may place too much trust on potentially incorrect recommendations from AI systems. Or maybe AI-assisted detection and prediction of enemy attacks would reduce the time for humans to make decisions, who make bad judgements as a result. Automated systems can also be complex and fragile, leading to unforeseen consequences.

Christian Calling

We believe there are strong biblical reasons why a Christian should work to reduce the risk of nuclear conflict. As Christians we are called to love our neighbours around the world, to promote peace and justice, to steward the natural world, and to govern with wisdom and prudence. Let’s apply each of these to nuclear security.

Peace

They will beat their swords into ploughshares and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation will not take up sword against nation, nor will they train for war anymore.”

⸺ Isaiah 2:4

The clearest argument for working on this problem is that Christians are called to bring peace to the world. “Blessed are the peacemakers”, as Jesus famously said in the Sermon on the Mount, “for they shall be called sons of God”. (Matthew 5:9) Christians should “first seek the kingdom of God and his righteousness”, (Matthew 6:33) and the kingdom of heaven will be a place of peace. The verse above from Isaiah has even inspired the names of the Christian anti-nuclear Plowshares Movement and Ploughshares Fund. As the body of Christ in this world, we yearn for a world like this and seek to change our world to be closer to the ideal kingdom that Jesus proclaimed.

Love

“The second is this: ‘Love your neighbour as yourself.’ There is no commandment greater than these.”

⸺ Mark 12:31

Fundamentally, reducing the burdens of nuclear risk shows love to our neighbours. It is good and right for Christians to provide security, food, health, and shelter for others, but the ongoing risk of nuclear war puts all of these in jeopardy. Whilst there is a clear Christian mandate to care for people’s needs today, is there not also a mandate to anticipate people’s needs tomorrow? Of course, it’s certainly more emotionally rewarding to serve people’s needs today, but the goal of Christian love isn’t our own satisfaction; it is obeying God’s command. The idea of helping potential billions of people might be rather abstract, but it might just be how God is calling you to love your neighbours and his creation.

Justice

“

Speak up for those who cannot speak for themselves,

for the rights of all who are destitute.

”

⸺ Proverbs 31:8

Christians are called to pursue justice. A nuclear war will never be just or proportional because there is no way to avoid mass casualties of innocent civilians and indiscriminate suffering all over the world. It is not fair that the decisions of a small number of powerful countries should affect all other countries, e.g. by threatening a nuclear attack. Whilst only 9 countries have nuclear weapons, 113 voted to ban nuclear weapons at the United Nations in 2016. If you live in a nuclear capable country, you should carefully consider your influence and responsibility compared to those who don’t. There is also a question of intergenerational justice. Improving nuclear security today creates a safer world for our descendants, but future generations have no ability to advocate for themselves. Some would argue that we have a duty to advocate on their behalf. 1

Stewardship of creation

“

I brought you into a fertile land to eat its fruit and rich produce.

But you came and defiled my land and made my inheritance detestable.

”

⸺ Jeremiah 2:7

A nuclear winter would be environmentally catastrophic. We are already seeing the disastrous effects of one or two degrees celsius of climate change. A nuclear winter could block enough sunlight to cause plants to die (including human crops) and ecosystems to collapse, potentially lasting for decades and with more northerly latitudes more extremely affected. Other studies suggest a nuclear winter could significantly damage the ozone layer, resulting in greater UV exposure and higher rates of cancer. This is not to mention the harms of radioactive material dispersed around the blast sites and into the upper atmosphere, and unpredictable effects of rapid global cooling on weather systems. Although much of the fissile material has a short half life, areas of intense radiation would likely remain—indeed, Chernobyl still has a 20 mile exclusion zone. Finally, it is important to remember that God’s creation includes cities as well as the natural world; a large nuclear war entails the physical destruction of cities, which constitutes a great tragedy both for us and for the Lord.

Submission and security in Christ

“

But I tell you, do not resist an evil person.

If anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to them the other cheek also.

”

⸺ Matthew 5:39

Christians are not just called to pursue peace; we are called to pursue peace in a distinctive, radical, and Christlike way. We are commanded to not resist an evil person and not to avenge ourselves. (Matthew 5:39, Romans 12:19) We are to bless those who persecute us and to love our enemies. (Romans 12:14, Matthew 5:44) We are to be the first ones to apologise and the first to forgive, just as Jesus first forgave us. (Ephesians 4:32)

To an outsider, these principles are naive and reckless. But a Christian has nothing to fear from violence and persecution in this world, because she knows that Jesus submitted himself to his enemies and rose victorious. She knows that God is sovereign, and there will be an ultimate judgement for those who do evil. Her security lies in God’s promises, not earthly weapons or power.

Some Christians use these principles to argue against certain nuclear weapon doctrines. Is it right to commit to deterrence (i.e. promising to strike back if someone strikes you)? Is it right to pursue unilateral disarmament (i.e. decommissioning your arsenal even if your enemy doesn’t)? Not all Christians agree on these questions and the Bible certainly doesn’t give explicit answers. We encourage you to prayerfully consider whether Christians should commit to nuclear disarmament or deterrence, and under what circumstances you feel these weapons could justifiably be possessed or used.

Wisdom and prudence

“

Do not put your trust in princes,

in human beings, who cannot save.

”

⸺ Psalm 146:3

The current system of military and government oversight of weapons systems is dangerously lacking. Much of the risk of a nuclear disaster is driven by the risk of misuse or accidents. But Christians who are called to govern and manage are called to do so with wisdom and prudence. Taking care in designing systems to avoid misuse or accidents, and managing weapons wisely and cautiously would go a long way to reducing the risk of a catastrophic outcome.

Moreover, Christians ought to have a deep mistrust of those in power. Time and again in the Bible and in the church, we see leaders fall victim to sin. Even the holy and blessed nation of Israel frequently became despicable in the sight of God. Often when thinking about military issues, it’s easy for us to think in terms of ‘us and them’, where we are the good guys and our enemies are the bad guys. Regardless of whether this is true right now, there’s no guarantee that this will always be the case. It’s not unthinkable that a rogue president or an extremist government could one day use nuclear weapons purposefully or accidentally. One might seek to reduce these risks through adding checks and balances or pursuing disarmament.

Christian Examples

Biblical examples

- One of the worst outcomes of a large scale nuclear war would be crop failure and famine. In Genesis, God uses his faithful servant Joseph to prevent famine in Egypt. Joseph was granted the gift of foresight and administration skills, which he used to oversee the storage of surplus grain and avoid a famine. Clearly God cares about preventing disasters, and he chooses humans like us to share this work with him. Another biblical example of preventing a deadly catastrophe can be found in the book of Esther. Although God’s voice doesn’t take front and center stage (compared to speaking to Joseph in dreams), we see how God uses Esther’s faith and royal position to achieve his plan to save the Persian Jews from genocide.

- Another biblical example of preventing a deadly catastrophe can be found in the book of Esther. Although God’s voice doesn’t take front and center stage (compared to speaking to Joseph in dreams), we see how God uses Esther’s faith and royal position to achieve his plan to save the Persian Jews from genocide.

Joseph used his government position to avoid a deadly famine

Christians today

Christians for Impact was recently lucky enough to interview Rose Gottemoeller, the first woman to hold the position of Deputy Secretary General of NATO. She helped to negotiate the New START arms control treaty between the US and Russia, signed in 2010. You can listen to an interview about her work and how her faith enabled her work on our Christians for Impact podcast.

Brian Green is an academic philosopher and ethicist at the Markkula Center of Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. He studies the ethics of emerging technologies, especially nuclear weapons. You can listen to an interview about his work on the Christians for Impact podcast.

We’ve also gathered a list of some Christian organisations doing great work to promote nuclear peace.

- Christian Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament - part of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), an organisation with a long and impactful history of campaigning against nuclear weapons in the UK

- Pax Christi International- A worldwide Catholic organisation working for global peace

- The Friends Committee on National Legislation - “A nonpartisan Quaker organization that lobbies Congress and the administration to advance peace, justice, and environmental stewardship”, based in the United States.

The National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) represents “more than 45,000 local churches from about 40 different denominations and serves a constituency of millions” and argues against first use, nuclear testing, hair trigger alert status, and argues for reductions of nuclear stockpiles.

Image credit: Oppenheimer, Universal Pictures

Reasons Not To Work On This

Theological

There are at least a couple of theological reasons why a Christian may not be persuaded to work to reduce nuclear risk.

You may believe that a nuclear war is such a big event in human history that it’s probably already a fixed part of God’s plan whether it happens or not. Jesus tells us to “not be anxious about the future”. More specifically, you might interpret God’s covenant with Noah to mean that a nuclear winter will never happen. “While the earth remains, seedtime and harvest, cold and heat, summer and winter, day and night, shall not cease.” (Genesis 8:22)

Moreover, one argument for preserving nuclear capabilities in the West is the doctrine of a just war, proposed by Thomas Aquinas. Sometimes the only way to maintain justice and order is to use force (e.g. most people agree it was right to resist Nazi Germany in the Second World War). Nuclear weapons can deter unjust regimes from expanding or committing atrocities, and sometimes we have to sacrifice peace in exchange for justice. On the other hand, it is not clear that nuclear deterrents could ever themselves be used justly or proportionately, given that they kill indiscriminately and at an enormous scale.

Practical and personal

It can be hard for an individual to find a job with a good chance of meaningfully reducing nuclear risk. Taking US nuclear policy careers as an example, there aren’t many jobs out there to begin with, and many of the roles that do exist could plausibly make the situation worse (e.g. working for a government or military). Therefore, because of this limited number of jobs, this path will not be for everyone. Indeed, professionals have noted that the nuclear policy field can feel quite insular and that there is a lot of gatekeeping.

Many of the most influential career paths are difficult to pursue if your primary goal in your career is to reduce nuclear risk. For example, it's probably difficult to become a military officer with control over nuclear weapons if your only motivation for the job is to prevent the use of nuclear weapons. You would need a huge amount of persistence and motivation to have an impact in this way, and that impact would be highly unpredictable and uncertain. You would need to avoid ‘value drift’ while immersed in a culture of people who don’t share your motivations, and you may even have to be dishonest about your motivations and beliefs in order to succeed professionally.

Your plan to reduce nuclear risk with your career may depend on influencing international relations and political systems. Achieving your desired outcome in these spheres is not at all guaranteed. You could spend years advocating for a policy, and then one day a war breaks out or a new government is elected and all your work is wasted. If you would be discouraged by repeated setbacks like this, then you might not be a good fit for roles in nuclear weapons policy.

That said, a Christian may be better suited to these kinds of challenges than others. Through the gospel we know that our strength and our worth doesn’t come from ourselves or our job, but from our identity in Christ. Your good works alone cannot and will not save humanity, just as they cannot save you. Whilst we are called to ‘work with all (our) heart, as for the Lord himself’ (Colossians 3:23), we know that salvation comes only by God’s grace. A career spent reducing nuclear risk will probably be competitive, taxing, demoralising, and possibly achieve nothing at all, but we must still have patience and faith that God will use our efforts for his glory. We are after all “created in Christ Jesus to do good works, which God prepared in advance for us to do” (Ephesians 2:10).

Ways To Help

Policy and policy research

Given that large nuclear weapon arsenals are owned and controlled by national governments, the most intuitive way to reduce nuclear risk is by influencing the actions and beliefs of these governments. This can be done from either inside or outside the government (although people frequently move between the two, in a so-called ‘revolving door’).

Careers inside government are typically either political (e.g. being an elected representative) or non-political (e.g. being a civil servant). Politicians generally have more control over the direction of government, but they face greater public scrutiny and aren’t guaranteed to win or hold power. Civil servants have more stable roles, and play a crucial role in advising and implementing policy, but are less likely to drive the policy agenda.

Careers outside government typically focus on researching, developing, and lobbying for certain policies. Lobbying and influencing roles are typically found within think tanks and charities/NGOs, and may involve activities such as meeting legislators, fundraising, and organising events. Research roles are typically within academia or think tanks such as the RAND Corporation or Nuclear Threat Initiative, and might involve collecting data or thinking strategically about nuclear doctrines and threats. Some researchers we spoke to recommend spending time in the government or the military beforehand, as some important insights relevant to strategy and policy are classified to outsiders.

If you want to try out a career in policy and policy research, we especially recommend the Scoville Peace Fellowship.

We recommend reading our profile on Politics and Policy for more information on all of these paths, and considerations of personal fit.

Suggested organisations in the USA

- Government departments:

- Department of Defense

- White House

- National Security Council

- State Department

- Think tanks and NGOs:

- RAND Corporation

- Carnegie Corporation of New York

- Longview Philanthropy

- Open Philanthropy

- Nuclear Threat Initiative

- Ploughshares Fund

- ICAN

Technical projects and research

There are a number of technical projects and research projects (some of which are promising and others more speculative) that we believe could either reduce the risk of nuclear war or mitigate the consequences. We think a wide range of scientists, engineers, operations professionals and generalists could contribute to these projects and we have described some of them below, with links for further investigation.

We want to give a particular shoutout to High Impact Engineers, who have put together a resource guide for engineers wanting to reduce the risks of nuclear war.

Artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, and the automation of nuclear command control and communications

Source: Ruhl (2022) “Autonomous Weapon Systems & Military AI”

“NC3” (Nuclear command, control and communications) refers to the plethora of digital systems used to operate nuclear weapons. Complex systems such as these are difficult and expensive to monitor and update, and therefore can be vulnerable to cyberattacks, bugs and errors. As digital technology progresses quickly, especially the recent boom in artificial intelligence (AI), it seems especially important to preemptively guard against future vulnerabilities.

Even without malign cyberattacks or further automation of NC3, improving NC3 reliability and security is critically important. A large number of nuclear ‘close calls’ have occurred throughout history, and the culprit is often faulty detection systems. Solar flares, moonrises, power outages, and even a black bear have all been falsely interpreted as potential nuclear attacks. We recommend reading through this list for more examples. If you have a relevant technical background, working to improve the reliability of these systems and procedures could make the difference between a close call and a disaster.

Cybersecurity is another crucial concern. In 2017, the US Defense Science Board wrote that “the offensive cyber capabilities of our most capable potential adversaries are likely to far exceed the United States’ ability to defend and adequately strengthen the resilience of its critical infrastructures”.

Food Security

Most of the risk of deaths in a nuclear war is the result of a hypothetical nuclear winter. Although a nuclear winter has never happened before, some scientists believe the worst effect would be a widespread famine. There are several scientific, engineering, and policy projects that have the promise of substantially reducing the number of hunger deaths in a nuclear winter. These focus on the technical challenges of producing food without sunlight, such as using enzyme reactions to break down the cellulose in wood to create digestible sugars, using seaweed that grows in low light, or breeding more resilient crops. Other projects investigate the political and economic challenges of storing and distributing food in a disaster scenario, potentially with a societal collapse. It’s also important to improve our models of nuclear winter food production, to better calibrate our precautions and to advocate to policymakers. Many of these projects are poorly researched and underdeveloped, which means there is a large opportunity to do an outsized amount of good.

We think The Alliance to Feed the Earth in Disasters (ALLFED) is doing excellent research in this field, and you can hear more about their work via this podcast and transcript, or their website.

Civilisational resilience

If a nuclear war caused most humans to die, then our civilisation would be in trouble. With a massive loss of manpower and expertise, we would be unable to sustain our complex systems and modern infrastructure like power stations or car factories. If we could help the survivors to recover those capabilities as quickly as possible, we could make the impact of the disaster significantly less worse.

Some experts have suggested that a ‘manual for civilisation’, physical shelters, or stockpiles, could help the survivors of a global catastrophe to rebuild faster. These ideas are highly speculative, and so far poorly researched, but there’s a small chance they could be incredibly important one day. These projects aren’t just valuable for nuclear disasters; they could also help survivors to recover from other disasters, such as a deadly pandemic or a coronal mass injection.

Our friends at High Impact Engineers have put together a guide on how you could use engineering skills to contribute to civilisational resilience projects.

Donate (especially in the near future)

One way you might be able to reduce the risks of nuclear war is by donating to effective civil organisations who try to reduce these risks. Your donations would typically fund policy research and policy advocacy — that is, finding and developing effective, politically acceptable ideas for reducing nuclear risk, and encouraging governments to adopt those ideas. This would typically be in the US, because civil organisations have influence over the US government (unlike more autocratic countries) and the US is a major nuclear player.

Why should you fund non-governmental organisations in the nuclear space? Civil organisations in the US have a track record of successfully developing initiatives and policies that reduce nuclear risk. Legislative and executive government officials don’t always have time to explore and develop policies, so civil society often takes on this role. One example is the cooperative threat reduction (CTR) approach pioneered by the Carnegie Corporation of New York in the 1990s. The Nunn-Lugar CTR programme then was passed by the congress, which led to vast numbers of warheads from post-Soviet states being eliminated, as well as usable fissile material and biological and chemical weapons materials.

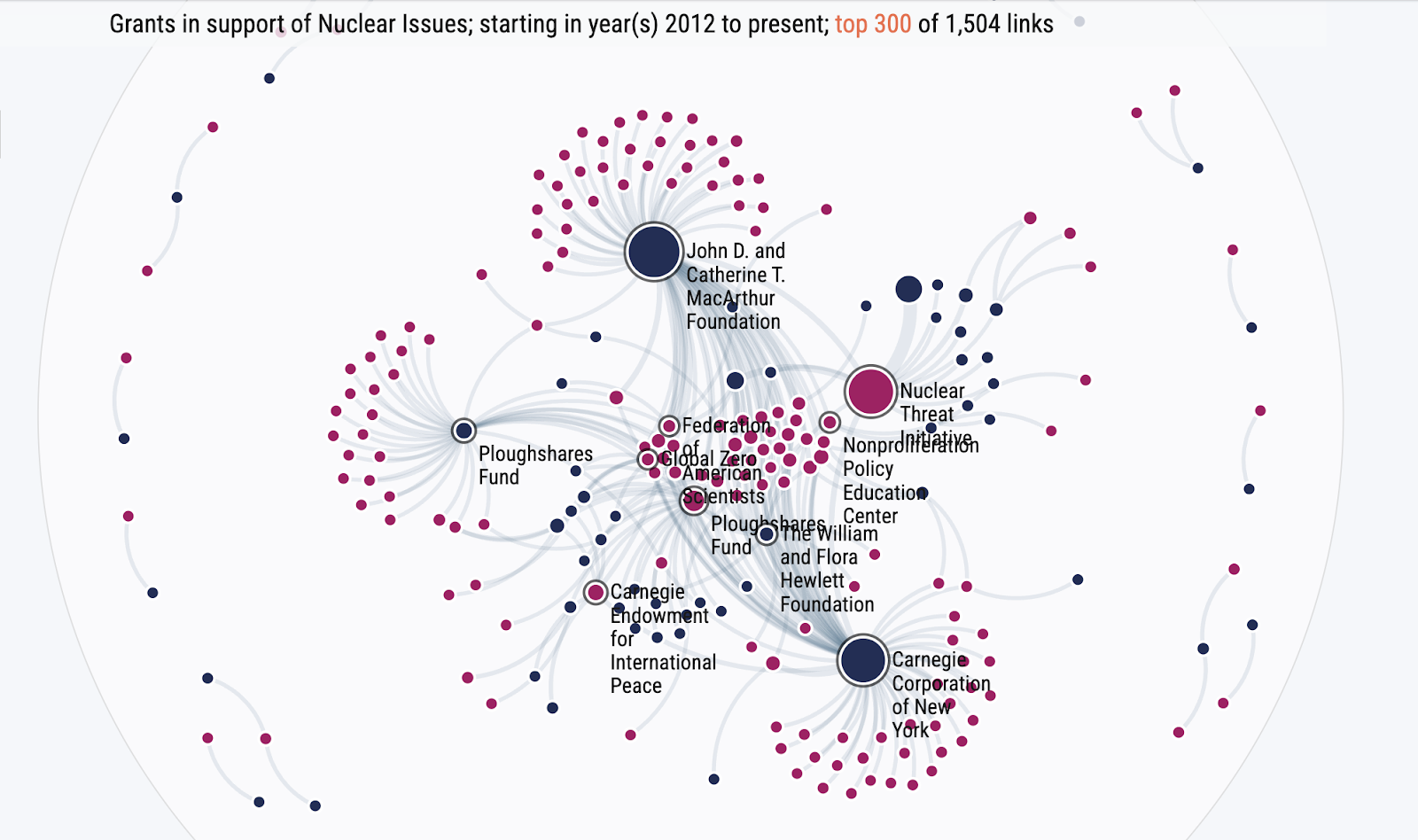

The MacArthur Foundation was the largest private funder of nuclear security work with grants of around $15 million per year between 2014 and 2020, around 32% of the total annual philanthropic nuclear security funding. In 2021, they announced that they would withdraw funding support, with final funds disbursed in 2023. The reasons for this have little to do with the importance or value of the work they funded, rather a change in internal strategy. This leaves a major funding shortfall. Some other funders have stepped in to narrow the gap, but not enough to close it. For comparison, the budget of Oppenheimer was more than twice as much as philanthropists currently spend on preventing nuclear war.

A map showing the importance of the MacArthur Foundation in nuclear philanthropy. From the Peace and Security Funding Map tool

With tensions building due to the Russia-Ukraine war and other conflicts, donations now could have particularly high leverage over the strategic direction of the field.

Donating now to plug temporary gaps in funding and to smooth out funding over time could be especially valuable because it avoids a break in the talent pipeline. If organisations cannot afford to retain staff or invest in internships or other outreach, then talented staff who would otherwise have worked on nuclear security may leave the sector entirely, causing a permanent loss.

That said, we don’t necessarily recommend building a career around purely earning money to donate to nuclear causes, because we have no reason to think this funding gap will exist in the medium future. The current funding shortfall is relatively small compared to total US philanthropic spending, so it’s very plausible that the gap will be closed soon. However, one benefit of an ‘earning to give’ career is that you can flexibly adjust your donations to meet temporary, specific needs like these, across a range of causes. 2

If you feel called to donate now or in the near future, we suggest considering Longview Philanthropy’s Nuclear Weapons Policy Fund.

Advocate

As discussed at the beginning of this article, we don’t believe nuclear risk receives as much attention as it should do. Specifically, we don’t think the salience and public awareness of nuclear risk is high enough compared to other global problems. It’s likely that greater public concern would (a) put pressure on democratic governments to take action and (b) encourage more talented professionals to pursue careers in nuclear risk reduction.

In the past, we have seen that popular activism has meaningfully influenced the behaviour of the US government. The Nuclear Freeze campaign in the early 1980s resulted in the Reagan Administration softening their rhetoric, a freeze resolution to be passed in the House of Representatives, and the start of negotiations between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev which eventually resulted in the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty of 1991. Leading or supporting mass movements today could be an effective way to reduce nuclear risk. Research by the Social Change Lab finds that popular movements can be highly effective in producing change in the right circumstances.

Even if you don’t think activism is for you, you might still be able to inspire others to have an impact. Even sharing resources or starting conversations with friends could raise the salience of this issue and inspire more people to work on this problem.

Journalism is another powerful way to raise awareness of issues like nuclear war. After the Hiroshima bombing of 1945, the US government attempted to cover up the true death toll and the awful effects of radiation poisoning. However, reporter John Hersey faked a stomach illness to sneak out of his hotel and meet survivors, resulting in a 30,000 word exposé being published in a special issue of the New Yorker. Without his reporting, the world might never have realised the true horrors of nuclear warfare. Nowadays, we think Vox’s Future Perfect section is a great example of journalism that focusses on neglected, important global problems. We also recommend the Tarbell Fellowship for those who are starting out in the field.

Who Are Some Christians In The CFI Network Working On This?

Rose Gottemoeller (CFI podcast interview here)

Tyler Wigg Stevenson

Interested in talking to a Christian expert about tackling nuclear security with your career?

Sign up for 1-on-1 mentorship. We’ll pair you with a Christian who can talk to you about how to make an impact on nuclear security.

Notes

-

This paper by John and MacAskill suggests how and why we might do this. ↩

-

If you are interested in strategies for optimal donations across time and across causes, take a look at Phil Trammell’s work here. ↩